Arguing, Round and Round We Go in a Couple Relationship

November 4, 2016

Several weeks ago, I met with a couple – Mary and Bob – I hadn’t seen in a month. “So how are things going, I asked wanting to check in before we got started. “I think we’ve taken five steps back from the last time we saw you,” said Bob. “We seem to be arguing about the same things we did a few months ago. It’s exhausting. I just can’t win.”

His wife was quick to point out that if he would just do what he said he was going to do – like come home on time, acknowledge her texts and be “involved” on the home front – things would be much easier. “I don’t ask for much,” she declared, “but I can’t do everything myself. Why can’t you just help out more?”

Bob began arguing back. “That’s not true! I made dinner for the kids the other night and folded the laundry but you said nothing. What do you want from me?”

Sound familiar? Without a doubt, this scenario, and its variations are played out in households across America.

The Enemy Dance

As we processed how both partners experience the conflict around home life, it became clear that the arguing could have been about anything – the pattern was always the same. Mary criticized and pushed in an attempt to engage Bob who withdrew to avoid being criticized or what he called entering “the kill zone”. The more Mary pushed, the more Bob withdrew – each fueling the fires of an ‘enemy dance’ that left both partners feeling disconnected. And the more they danced the same old steps, the more stuck and hopeless they felt.

As we unpacked their dance, both partners came to realize that their negative cycle was fueled by emotions that ran far deeper than who did the laundry or cooked dinner. Mary believed Bob was disinterested not only in their family but in her. As we peeled back the onion, she admitted that every time he failed to follow through, she gathered more evidence that what she believed was true – she was unimportant and couldn’t count on her husband as a partner. We also learned that as a child, Mary felt unvalued and invisible to her parents, a wound she carried as an adult. So when Bob withdrew, the music from that childhood experience began to play. Until they came to therapy, Bob had no idea that Mary was triggered each time he forgot to call home. When Mary shared her fear of not being enough for Bob, he softened and acknowledge he had no idea she felt that way. It opened the door for further understanding and flexibility in their dance as Mary could identify how she was triggered, understand where it came from and lean towards Bob for reassurance.

Bob on the other hand, grew up in a quiet family where feelings weren’t openly expressed so when Mary criticized, he became anxious and withdrew. Mary didn’t know that Bob felt emotionally unsafe when they were in an escalated cycle, so he ‘hid’ until it was safe to come out. The more he hid, the more anxious Mary became and so she pushed harder, arguing with him. The harder the push, the deeper the withdrawal generating more anxiety in the pursuer who pushes again harder. The cycle fueling the fires of a dance that hijacks them both into despair and pain.

Arguing and the Patterns

So where do we learn these patterns? Fifty percent of how we engage in primary relationships can be traced back to what we learned in our family of origin. Those experiences and those from former relationships shape the expectations and assumptions we make in our primary relationships with our partners. You may recognize those patterns as they are played out from one generation to another. One client confessed she was terrified of marriage for fear that she would have to relinquish her friendships and “end up like her mother” who she perceived to be lonely and miserable.

Think about it. What were the unspoken rules about emotional expression in your family? Who made you feel safe and loved? How did your parents express affection? How did they argue?

Do you have a question about a relationship issue? Contact The Montfort Group in Plano to learn more about addressing your patterns.

(Disclaimer: Names and any identifying information has been changed)

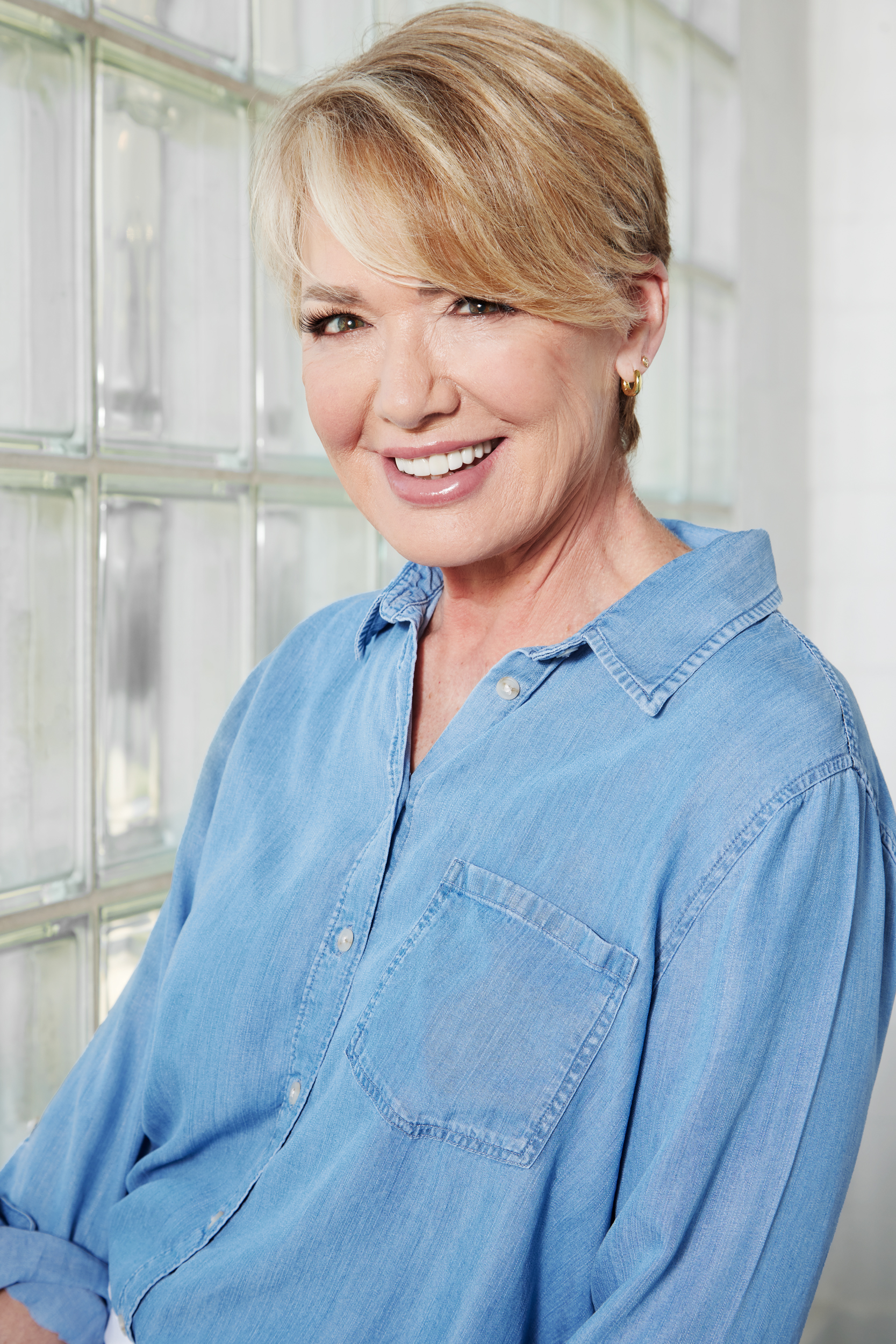

Laurie is a Licensed Professional Counselor with her Masters of Science in Counseling from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, TX. She is also a graduate of McGill University in Montreal. She received advanced practical training in Emotionally Focused Therapy for couples and families at UT Southwestern, where she spent five years in the Department of Psychiatry’s Family Studies Clinic working with diverse clients of all ages. In addition, she has completed training in Collaborative Law for couples seeking divorce to find solutions in a more amicable way.

accept

We use cookies to improve your browsing experience and ensure the website functions properly. By selecting 'Accept All,' you agree to our use of cookies.

© Tmg XXXX

Contact our office:

Already working with a Montfort Group clinician?

You can book or manage your next session here.

Stay Connected

Schedule Now